Why has the U.S. produced a magnificent Holocaust Memorial Museum before opening an institution of equivalent stature dedicated to slavery and segregation?

April 17, 2008

Op-Ed Columnist

By ROGER COHEN

ATLANTA

I was wandering through the King Center here when I stumbled on a movie clip of an indignant African-American woman saying: “If we can’t live in our country and be accepted as free citizens and human beings, then something’s the matter with something — and it isn’t me.”

That seemed a good, plain summation of the central conflict that has roiled American life since the nation’s foundation, through slavery and segregation and their bitter legacies. When this anonymous woman spoke, less than a half-century ago, she was an unfree American. How she was schooled, where she could sit and whom she could marry were matters determined by her race.

This “something’s the matter with something — and it isn’t me” is a big subject, the nation’s “original sin,” in Barack Obama’s words. It’s also a painful one that sees American ideals and practices at some remove from each other in ways of which Abu Ghraib was a reminder.

For nations to confront their failings is arduous. It involves what Germans, experts in this field, call Geschichtspolitik, or “the politics of history.” It demands the passage from the personal to the universal, from individual memory to memorial. Yet there is as yet in the United States no adequate memorial to the ravages of race.

The King Center is a fine institution. But it’s a modest museum, like others scattered through the country that deal with aspects of the nation’s most divisive subject. Why, I wondered as I viewed the exhibit, does the Holocaust, a German crime, hold pride of place over U.S. lynchings in American memorialization?

Let’s be clear: I am not comparing Jim Crow with industrialized mass murder, or suggesting an exact Klan-Nazi moral equivalency. But I do think some psychological displacement is at work when a magnificent Holocaust Memorial Museum, in which the criminals are not Americans, precedes a Washington institution of equivalent stature dedicated to the saga of national violence that is slavery and segregation.

I lived in Berlin for three years, a period spanning the Bundestag’s decision in 1999 to build a Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. The debate, 54 years after the collapse of Hitler’s Reich, was fraught. It takes time to traverse the politics of history, confront guilt and arrive at an adequate memorialization of national crimes that also offers a possible path to reconciliation.

Germans have confronted the monstrous in them. In the end, they concluded the taint was so pervasive that Degussa, which was linked to the company that produced Zyklon-B gas, was permitted to provide the anti-graffiti coating for the memorial. The truth can be brutal, but flight from it even more devastating.

America’s heroic narrative of itself is still in flight from race. The decision, approved by Congress in 2003, to build the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, to open in 2015, reflects a desire to plug this hole in the nation’s memory. But what this $500 million institution will be remains to be invented.

“The Holocaust is a horribly difficult subject, but the bad guys are not Americans,” Lonnie Bunch, the museum’s director, told me. “Race, however, is the quintessential American story and one that calls into question how America defines itself and how we, as Americans, accept our own culpability.”

He continued: “I am confident that the U.S. public can now do that. My challenge is to express not only the lynching, but also the resiliency and spirituality that are part of the core American identity.”

I also think America’s ready, a half-century after the civil rights movement, for this painful memorialization. But it won’t be easy. The aborted International Freedom Center museum at ground zero, conceived to showcase liberty but dismissed by some as camouflage for a liberal agenda, shows how explosive the politics of history are.

“Memory,” the French historian Pierre Nora noted, “is life.” As such, it’s subject to violent swings.

It’s striking how the three contenders for the presidency offer different self-images for America. John McCain comforts the classic heroic narrative. Hillary Clinton breaks the male hold on that narrative and so transforms it. Obama transfigures it in another way by personifying America’s victory over its most visceral blemish.

The world is weary of the narrative of American exceptionalism. Something’s the matter with something. Guns and God, Hillary’s latest mantra, won’t set America right. Nor will 100 years in Iraq.

It’s time for the country to ask itself some hard post-jingoistic questions and allow the memorialization of its darkest chapters. To demand truth commissions of other nations, while evading them at home, is unhelpful.

In committing to a major museum of African American History, and propelling the first serious African-American presidential candidate, the United States is recasting the psychology of its power. That’s scary. It can also be salutary.

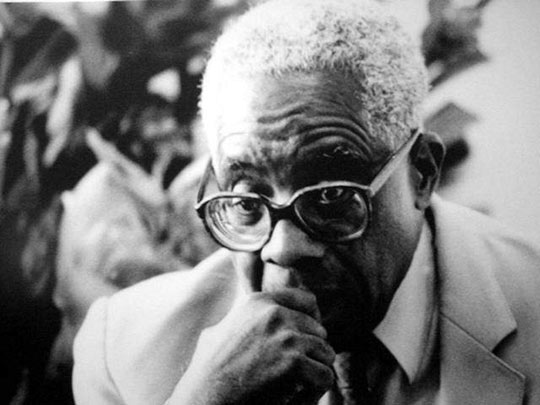

Another former student of Prof. E. Bradford Burns, Dr. Rosa María Pegueros, sent me this photo of the late great "Querinologist" and historian. Among many other publications, he wrote a bibliographic essay titled "MANUEL QUERINO'S INTERPRETATION OF THE AFRICAN CONTRIBUTION TO BRAZIL", The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Jan., 1974), pp. 78-86

Another former student of Prof. E. Bradford Burns, Dr. Rosa María Pegueros, sent me this photo of the late great "Querinologist" and historian. Among many other publications, he wrote a bibliographic essay titled "MANUEL QUERINO'S INTERPRETATION OF THE AFRICAN CONTRIBUTION TO BRAZIL", The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Jan., 1974), pp. 78-86